밤에도 그것은 언제나 그곳에 있다

Night Holding Space Even at Night

2022. 5. 27. – 6. 19.

INYOUNG GALLERY (Seoul, Rep. Korea)

Preface and Critic | Yeji Hong

English Translation | O Woomi Chung

Photographer | CJYART STUDIO

Video | Yoonsuk Choi

Designer | CMYK

Host Organizer Hyuho Kim

Supported by Arts Council Korea (ARKO)

서문 | preface

서문

김현호 개인전 《밤에도 그것은 언제나 그곳에 있다》

「어둠 안에서 열리는 눈」

홍예지

미술비평가, 독립 큐레이터

산등성이를 타고 밤이 깔린다. 수백 번의 붓질이 지나간다. 마른 짐승의 등골처럼 움푹 패인 곳이 있는가 하면, 우둘투둘하게 솟아난 곳도 있다. 튀어나온 자리마다 희미한 은빛이 감돈다. 저만치 위로 폭포 소리가 들린다. 솨아아- 떨어지는 물줄기는 빛줄기가 되어 어둠의 베일을 들춘다. 수심(水深)은 마음의 깊이와 같고, 수천 개의 물방울이 측정할 길 없는 심연으로 스며든다.

김현호의 산수(山水)는 견고한 표면 너머로 “심리적인 배면(背面)”[1]을 간직하고 있다. 겹겹이 도포한 카본 블랙 층 아래에는 오직 흑과 백으로 구성된 자연이 존재한다. 눈을 현혹하는 색들을 미련없이 걷어 내면서 맞아들인 세계다. 비움으로써 고요해진 화면은 화려함 대신 깊이를 얻었다. 그 깊이, 미세한 명암의 차이에 따라 무수한 사이-공간이 열린다. 관객은 저마다 마음이 이끄는 곳으로 걸어 들어간다. 한 사람 한 사람의 마음속 사원(寺院)에 불이 들어온다.

이 명상적인 그림들은 낯선 세계를 열어 보이면서 동시에 거두어 들인다. 언뜻 나타난 세계는 백일하에 드러난 자연이 아니다. 숨 멎는 암흑 속에서 은밀히 빛나는 자연이다. H. 롬바흐의 말마따나, 빛에 대한 감수성이 예민한 사람은 낮의 빛보다 아침의 빛을, 아침의 빛보다 밤의 빛을 높이 평가한다. “밤이 낮보다 더 근원적이지 않은가? 빛이 빛일 수 있기 위해서는 결국 보다 광대한 어둠으로부터 빛나 오르는 것이어야만 하지 않는가? (…) 존재는 모든 것에 선행하는 무에 대항하면서 자신을 두드러지게 함으로써 비로소 존재하는 것이 아닌가?”[2] 김현호의 화폭에서 산과 폭포는 어둠으로부터 “융기”한다. 이는 곧 “부활”이며, “내 마음대로 다룰 수 없는 것, 타자인 것, 사라지는 도중에 있는 것이 몸 자체 안에서, 몸으로서 돌출하는 것이다.”[3]

그림 속 자연은 접촉을 유도하면서 밀어낸다. “나를 만지지 마라.” 헤르메스적 시인의 눈을 가진 관객은 “이해(verstehen)”하지 않는다. “그는 본다.”[4] 이 무지막지한 어둠, 깊이를 가늠할 수 없는 미지(未知)의 영역을 그저 받아들인다. 이 역설은 타자와 나, 자연과 인간 사이에 신성한 거리를 설정하는 문제와 관련된다. “어떤 물러남, 거리, 변별 그리고 ‘측정할 수 없음’을 보여주는 것이 있는 곳이라면” 어디든 나타난다.[5]

내가 모르는 세계가 있다는 것, 밤이 오지 않을 수 없다는 것, 빛보다 어둠이 근원적이라는 것. 이 자명한 사실을 보다 편안한 마음으로 인정할 수 있을까? 서구의 몇몇 사상가들이 주장했던 것과 달리, 자연의 존재 여부는 나의 인식에 달려 있지 않다. 자연은 온전히 거기에 실재한다. 내가 바라보거나 말거나, ‘언제나 그곳에 있다.’ 자연의 절대적인 출현 앞에서 우리는 말문이 막힌다. 이해를 넘어서는 지점을 목도한다. 그럼에도 두렵지 않다. 우리의 몸을 천천히 감싸는 어둠에서 빛다운 빛과 조우할 수 있기에. 그렇다면 더 이상 “어둠 속에서 보는 게 문제가 아니다. 더 나아가 어둠에도 불구하고 보는 게 문제가 아니다(…) 중요한 것은 어둠 안에서 눈을 여는 것이다.”[6]

[1] 르네 위그, 『보이는 것과의 대화』, 곽광수 옮김, 열화당, 2017, p.117.

[2] H. 롬바흐, 『아폴론적 세계와 헤르메스적 세계』, 전동진 옮김, 서광사, 2001, pp.38-39.

[3] 장-뤽 낭시, 『나를 만지지 마라』, 이만형∙정과리 옮김, 문학과지성사, 2015, p.33.

[4] H. 롬바흐, op. cit., p.35.

[5] 장-뤽 낭시, op. cit., p.29.

[6] ibid., p.76.

Preface

Hyunho Kim’s Solo Exhibition : Night Holding Space Even at Night

Eyes That Open Up in the Darkness

Yeji Hong

Art critic

The night falls on the ridges of mountains. Hundreds of brush strokes carve the valleys that resemble the backbones of a bony beast and erect crests that protrude. Faint light quietly shimmers in every bumpy spot. The sound of a waterfall comes from above. The gush of water becomes a beam of light and unveils darkness. The depth of it is that of one’s heart, and thousands of droplets seep into the boundless abyss.

Hyunho Kim’s landscape paintings have a “psychological context”[1] beyond the solid surface. Underneath the layers of carbon black lies the black and white nature, which forsaking seductive colors gracefully let in. The canvas made silent by emptying attains depth instead of splendor. Countless in-between spaces are then open, depending on the depth and subtle brightness. Each audience follows their heart and the temple of their heart is lit up.

These meditative paintings open up a foreign world and take it in at the same time. The glimpse of it hints not at the self-evident nature, but the one that clandestinely glistens in the breathless darkness. As Heinrich Rombach put it, those who are sensitive to light value the light of morning over that of day and the light of night over that of morning. “Isn’t night more fundamental than day? For light to be light, doesn’t it ultimately have to be radiating from ample darkness? (…) Don’t beings exist by resisting nothingness(Nichts) that precedes everything and by surfacing?”[2] In Kim’s works, mountains and waterfalls are viewed as “uprising(surrection)” from darkness. It is “resurrection”, and “the sudden appearance of the unavailable, of the other and of the one disappearing in the body itself and as the body.”[3]

Nature in the paintings induces push and pull. “Touch me not.” Viewers with the eyes of a hermetic(hermetisch) poet do not “understand(verstehen)” but “see(sehen).”[4] They simply accept this wild darkness and the unknown realm of which the depth cannot be fathomed. This paradox is related to the issue of establishing the sacred distance between the other and I and between nature and man, and it is present “wherever there is withdrawal, distance, distinction, and the incommensurable”.[5] Can we accept these self-evident facts more naturally — that there is a world that is unidentified, that night cannot not come, that darkness is more fundamental than light? Contrary to what some Western thinkers have stated, the existence of nature does not depend on our perception — nature is wholly present. Whether or not one sees it, it is ‘always there.’ Before the absolute emergence of nature, we remain speechless.

Viewers see a point that lies beyond understanding, but they are not afraid since they are to come across true light in the dark that will slowly blanket their body. Then, “it is not a question here of seeing in the darkness, that is, in spite of it. It is a question of opening ones’ eyes in the darkness.”[6]

[1] René Huyghe, Ideas and Images in World Art: Dialogue with the Visible, trans. Gwangsu Gwak, Paju: Youlhwadang, 2017, p.117.

[2] Heinrich Rombach, The Apollonian World and the Hermetic World, trans. Dongjin Jeon, Paju: Seokwangsa, 2001, pp.38-39. (Translator’s note: The quoted text is a translation of the Korean edition.)

[3] Jean-Luc Nancy, Noli me tangere: On the Raising of the Body, trans. Sarah Clift, Pascale-Anne Brault, and Michael Naas, New York: Fordham University Press, 2008, p.15.

[4] Heinrich Rombach, op. cit., p.35.

[5] Jean-Luc Nancy, op. cit., p. 14.

[6] ibid., p.42.

작가노트 | Artist Statement

불이 다 꺼진 새벽 시간, 옥상에 올라 뒷산의 풍경을 바라보곤 한다. 어둠 속 어렴풋이 드러나는 산의 풍경을 지긋이 바라보면 숨어 있던 시각의 예민함이 살아나면서 낮에는 할 수 없는 방식의 교감이 시작된다. 그리고 나와 산 사이의 가시광선이 사라진 공간으로 무의식 속에 숨어 있던, 서술할 수 없는 무한한 서사가 생성된다.

2020년 사회적 격리로 인한 반작용으로 자연에 대한 향수를 느끼면서 이를 회화로 소환하기 시작했다. 한국화에서 그리는 유토피아는 대부분 자연을 담고 있다. 한국화 적 미감이 체화되어 있기에 이러한 상황에서 자연이 떠오른 것은 우연이 아닐 것이다.

흑백의 아크릴 물감에 헤비바디 미디움을 섞어 마티에르를 내어 그려진 대자연의 그림은 일종의 신체를 가지게 되고 현실의 오브젝트로 내 앞에 나타난다. 정지된 이미지가 담긴 이 평면의 물체 위에 묽은 카본블랙 물감을 도포한다. 어둠이 요철 사이사이에 흘러 들어가게 되면 그림은 다시금 시간이 흐르게 되고 나와 같은 위상을 가지게 된다. 그리고 비로소 자연은 새로운 몸을 가진 접촉 가능태가 되어 내 앞에 ‘존재’하게 된다.

이것은 “그림 연구”의 2부로, 직접 대면하고 싶은 것을 그림으로 소환하여 그것과 함께한 시간을 기록하는 그림연구 1부 “소환프로젝트”의 연장이다. 그리고 이것은 먹, 배접, 공기 원근법, 물의 시간성 등 한국화의 개념을 확장, 변형한 새로운 소환술이다. 이를 통해 현 시점에서 생각하는 ‘그림이란 무엇인가?’에 대한 질문에 나름의 답을 하고자 한다.

At dawn when all the lights are off, I often go up to the rooftop and look at the mountains that surround me. The scenery that slowly looms in the dark awakens the sensitivity, and the type of communion takes place that is not possible during the day. Between me and the mountains where the visible ray has vanished lies the creation of an unconscious, infinite, indescribable narrative.

In 2020 when social distancing made me feel nostalgic for nature, I began to summon it in my paintings. Most of the utopias depicted in Korean paintings include nature. As Korean aesthetics are embodied in me, it is not a coincidence that nature has occurred to me as a subject matter.

Paintings of mother nature, painted with matière with heavy body medium mixed with black and white acrylic paint, get to have a body and come into being as an object. A thin layer of carbon black is applied over this two-dimensional object containing a still image. When darkness streams in between the irregularities, time flows again, and the paintings and I are synced time-wise. Finally, nature ‘exists’ before me with her corporeal presence.

This is the second part of “Geurim Research” that follows “The Summoning Project” which records the time that participants have spent with the person they summoned as a painting. This is a new summoning technique that expands and transforms the concept of Korean painting such as ink, drawing board, aerial perspective and temporality of time. Meanwhile, it is an ever-updating answer of mine to the question ‘what is painting?’

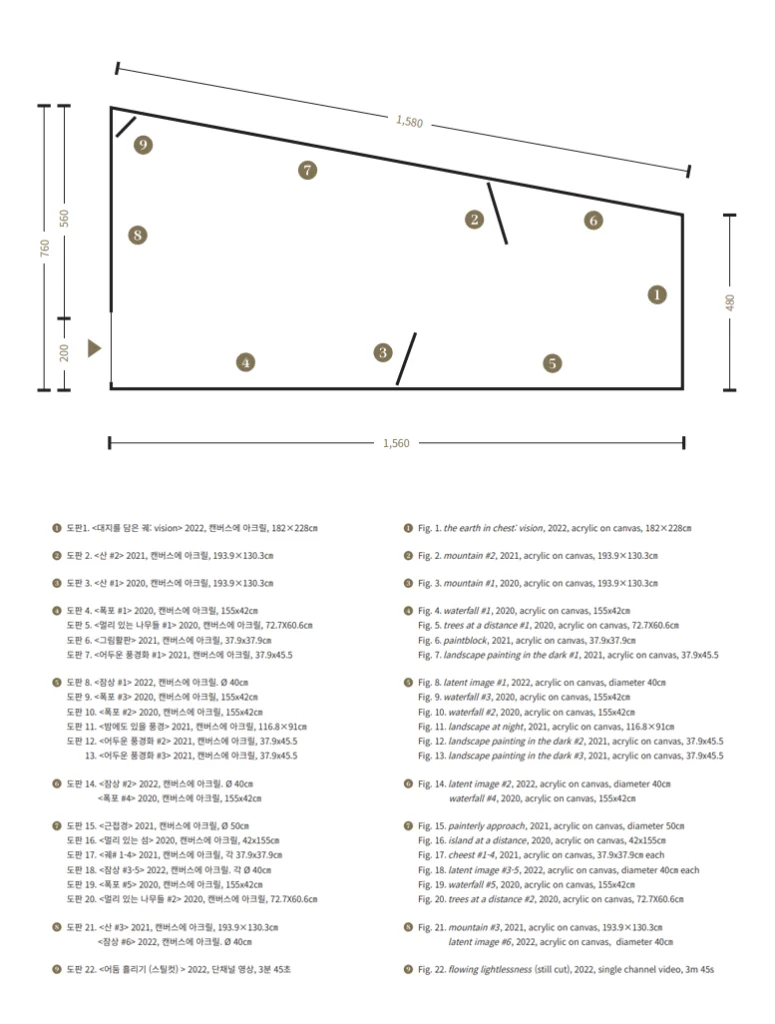

도면 | Floor Plan